ICTP is exploring how to harness the endless possibilities of 3D

printing for science, education and sustainable development. Its

Science Dissemination Unit (SDU), which has a long history of

introducing low-cost technologies to scientists in the developing

world, recently organized ICTP's first International Workshop on

Low-Cost 3D Printing for Science, Education and Sustainable

Development (6 to 8 May 2013).

The workshop gave a glimpse of the many possibilities the

technology provides to science, education and sustainable

development. Lecturers included William Hoyle, chief executive of

techfortrade, a non-profit organization established in 2011 to

support innovation in emerging technologies that facilitate trade

and alleviate poverty in the world's poorest communities. Inspired

by the glowing media reports on 3D printing, Hoyle thought the

technology could be promoted by his organization. "I was wondering,

what could 3D printing do for the developing world?" he said.

To answer that question, techfortrade launched the 3D4D

competition in 2012, inviting ideas from around the world for 3D

printing projects that would benefit society and have a sustainable

business plan. They received 78 entries vying for the $100,000

prize. The Washington Open Object Fabricators (WOOF), whose project

recycles waste plastic into filament for 3D printers to create new

products, submitted the winning entry. WOOF's proposal included a

plan to work with the non-governmental organization Water for

Humans to address water and sanitation issues in Oaxaca,

Mexico.

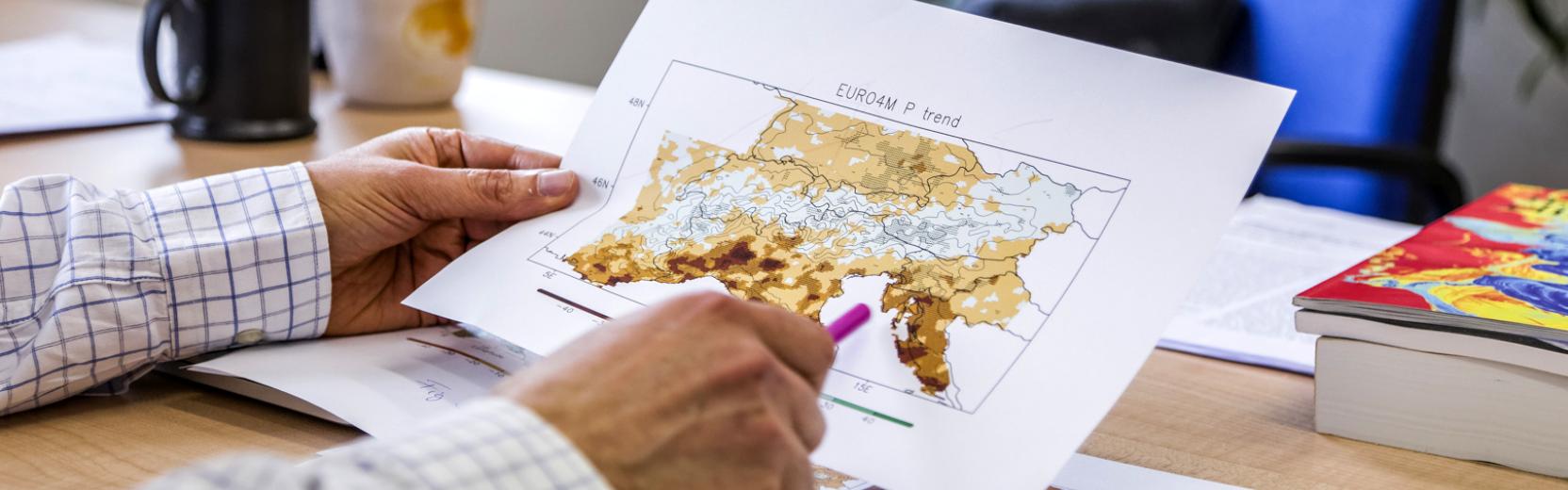

Gregor Luetolf of the University of Teacher Education in Bern,

Switzerland, trains teachers in new technologies. His presentation

at the ICTP workshop highlighted the many 3D printing applications

in education, including the designing and printing of musical

instruments, the production of reliefs for geography lessons, and

the creation of molecular models for science studies. The use of 3D

printing can be invaluable in geometry classes, he said, where

students often have difficulties visualizing objects presented to

them in a textbook. "If the students can design the geometric

object and then 3D print it and take it in their hands and really

hold it, they will have a better understanding of the dimensions of

the object," he explained.

Three-dimensional printing is also making its mark in the world of

palaeontology, where not only the printing itself but also the

scanning necessary to create digital models to be printed is being

used in creative ways to reach out to the general public.

Louise Leakey, a palaeontologist who concentrates her work in the

Turkana Basin area of Kenya, curates a virtual museum of African

fossils. At the ICTP workshop, she described how she uses a

technique called photogrammetry to photograph fossil specimens from

all angles; the photographs are then transformed into 3D images. At

the museum's website, www.africanfossils.org, users

can explore a number of hominid fossils and other specimen

collected from the Turkana Basin; a user-friendly interface allows

users to rotate fossils and view them from any angle. "This

interaction is getting people to think about our past again, and

that is exciting," Leakey said. She plans to make available

low-resolution files of some of these digital models on her website

so that users can print them on home 3D printers. For those who do

not have such printers, Leakey has designed a series of templates,

based on the digital models, that can be traced onto and cut out of

corrugated cardboard and then assembled, layer by layer, forming a

cardboard reconstruction of a fossil.

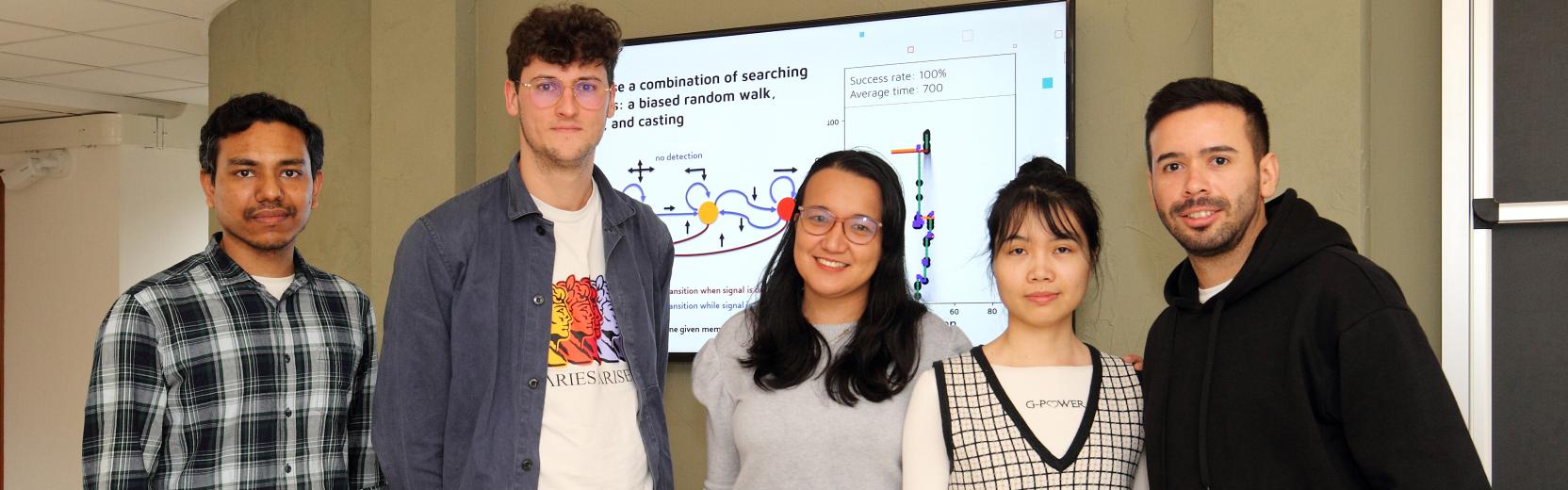

ICTP's workshop presented a range of 3D printing possibilities

that most of the participants and lecturers could never have

imagined before, and reinforced the notion of an open community

whose members are supporting each other with a fledgling technology

that is ready to take the world by storm. As with all of ICTP's

activities, the workshop brought international scientists together

and allowed them to create networks. Workshop participant Rodrigo

Marques, a chemistry professor at the State University of São Paulo

(UNESP), Brazil, connected with a fellow Brazilian attendee over

their shared interest in using 3D printers to construct bones; the

two hope to organize a 3D printing workshop in Brazil.

Those at the workshop expressed pleasant surprise at the wide

range of fields represented at the event, as well as the strong

camaraderie that developed during the 3 days between participants

and lecturers. "The atmosphere of the workshop was wonderfully

open," reflected participant Franco Policardi of the University of

Ljubljana, adding, "3D printing is like a multifunctional

algorithm, where there are a lot of different structures that have

to be implemented. The technology allows us to put all these small

parts of knowledge and technology together to create new things."

He predicted that 3D printing is poised to be around for a while:

"I do not think it passes one or two seconds after its Big Bang--we

are exactly at the beginning."