Are humans changing the length of the agricultural growing season or the number of extreme weather events? Are temperature and precipitation swings in one region of the world related to those in another? These are among the real-world research problems young scientists are examining at the first World Climate Research Program (WCRP)-ICTP Summer School on Attribution and Prediction of Extreme Events.

"Extremes are a hot topic," said Francis Zwiers of the University of Victoria in Canada, one of the school's co-directors. In fact, understanding, predicting, and attributing extreme weather events is one of the six "Grand Challenges" identified by WCRP, the organization that coordinates the international climate research community. Sonia Seneviratne of ETH Zurich, Switzerland, is the other co-director of the school and co-chair of WCRP's GEWEX project on the global energy and water budget, the WCRP project leading the Grand Challenge on extreme events.

With this Grand Challenge in mind, the ICTP school is one of many activities with which the WCRP hopes to make research headway. One of the school's main goals is mentoring PhD students, postdoctoral researchers, and early-career scientists from around the world on how to use new computational tools, said Anna Pirani of CLIVAR, WCRP's ocean-atmosphere research project, and another co-organizer of the school.

The topics covered in the school's lectures include both the basics and the most recent advances in climate science and statistics. They feature such issues as the simulation of climate extremes in long-term predictions and shorter term seasonal predictions and expose students to the ways that climate modelers and statisticians approach the topics differently. "WCRP brings teaching and mentoring on state-of-the-art research topics," Pirani said, highlighting how the school's instructors are leaders in the international research community.

In the afternoons, students work in groups of five on research problems that have been carefully prepared by the lecturers in such a way that they could very likely lead to " interesting results that could be pursued further," Pirani said. If the participants continue to collaborate with each other after the two weeks of the school are over, the organizers expect that their results could ultimately contribute to the peer-reviewed research literature. Such long-term projects, begun at the two-week school, are made possible through the use of open-source data and software tools, part of the legacy of the school once it is over, Pirani explained.

Organizers from both WCRP and ICTP believe that the school has the potential not only to further climate science, but also to help both organizations expand their reach.

"WCRP has lots of tentacles. They can reach other areas of the science community," said ICTP scientist and local organizer Adrian Tompkins, who has noticed that the collaboration has already increased ICTP's visibility in North America and Europe. Since the WCRP is able to fund students from around the world, the school has a "completely different flavor," he said. "For the first time, the limitation on the number of participants is not because of funding, but because of the choice to form tight, high-quality participant groups for the research component of the course."

ICTP, on the other hand, contributes its long-standing experience in international training activities to the partnership. One of many sources of inspiration for the school was Seneviratne's ICTP experience. The ICTP training school she attended in 2002 "was certainly an important experience for me," she recalled, and the two-week course gave her time to develop ideas she could later use in her own research.

Seneviratne said ICTP's support of capacity building and its expertise in engaging scientists from around the world is a major contribution. It provides an important opportunity for WCRP to expand the reach of its activities, increasing its involvement in capacity growth in the developing world

For Seneviratne, including people from so many different countries is one of the school's great strengths. The 35 applicants selected, out of a pool of 236, represent each region of the world. Pirani hopes that the diversity of the participants will lead to "lasting relationships across students and faculty." From his prior organisational experience, Tompkins added that the connections students make at such a school can forge "relationships for a scientific lifetime."

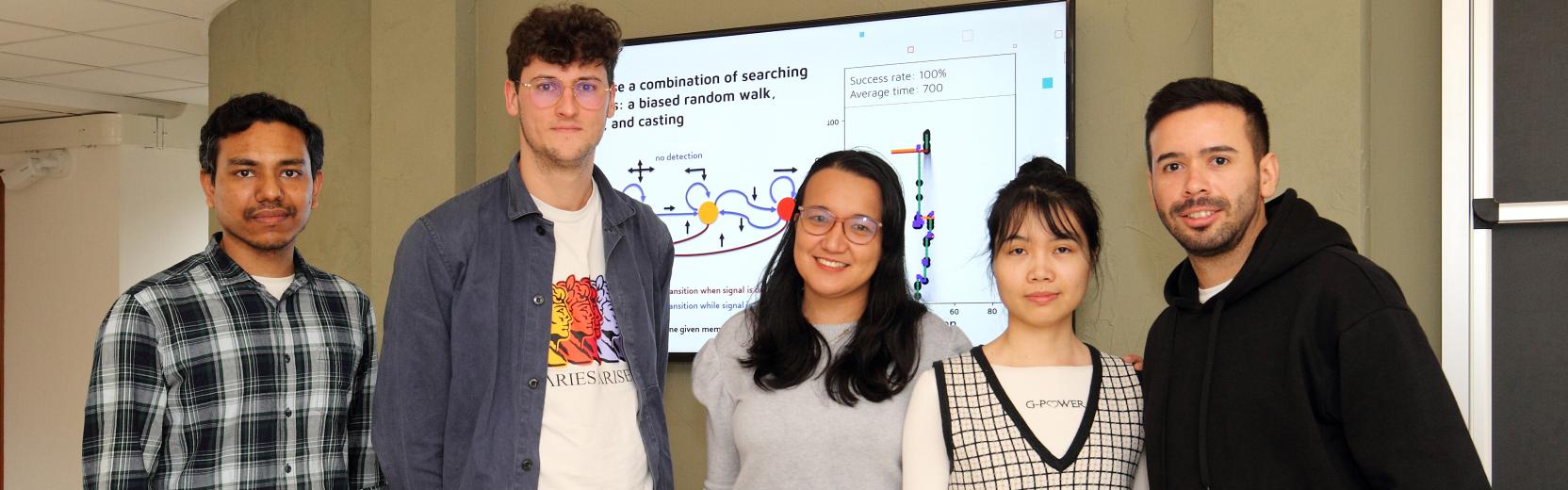

"It's extremely diverse, with students from different research groups all around the world," said Karthik Kashinath, a PhD student from India currently working at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in the United States. At the school, he and his project teammates, who hail from Germany, Burkina Faso, Iran, and Australia and are led by researchers from Spain and the USA, are investigating how to predict the frequency of events on seasonal scales.

On Friday afternoon, halfway through the school, the teams of students presented their work to their peers. The audience, sipping orange juice and nibbling on cookies, posed sharp questions that led to lively discussions among participants and lecturers. Each team ended their 10-minute presentation with a long to-do list for future research. Clearly, there is still plenty for the young scientists to accomplish to meet the WCRP's Grand Challenge, but armed with the school's lessons they are already well on their way.