On 28 September 2011, a member of the Gran Sasso National Laboratory's OPERA research collaboration visited ICTP to present the team's findings on superluminal neutrino velocity. The published results have created lively debates in the physics community because the team claims to have detected the neutrino speed to be faster than that of light.

Alexei Smirnov, senior researcher at ICTP and a prominent figure in the world of neutrino physics, explains why the OPERA results should be looked at critically and what possible directions future investigations could take.

"Neutrino physics is full of anomalies, which appear and disappear from time to time," he says, "And, as far as the results of the OPERA experiment go, there are many subtle points that need further investigation."

To begin with, says Smirnov, experimental physicists will definitely continue to check for any systematic errors in measurements. And why is it considered so plausible that systematic errors could have crept in? "The OPERA results show that the neutrino velocity is 60.7 nanoseconds faster than light, but they have arrived at this figure by subtracting comparatively large values of time delays, which are at much higher scales than nanoseconds, and very long proton bunches" he says. This means the precision of the final result is subject to doubt.

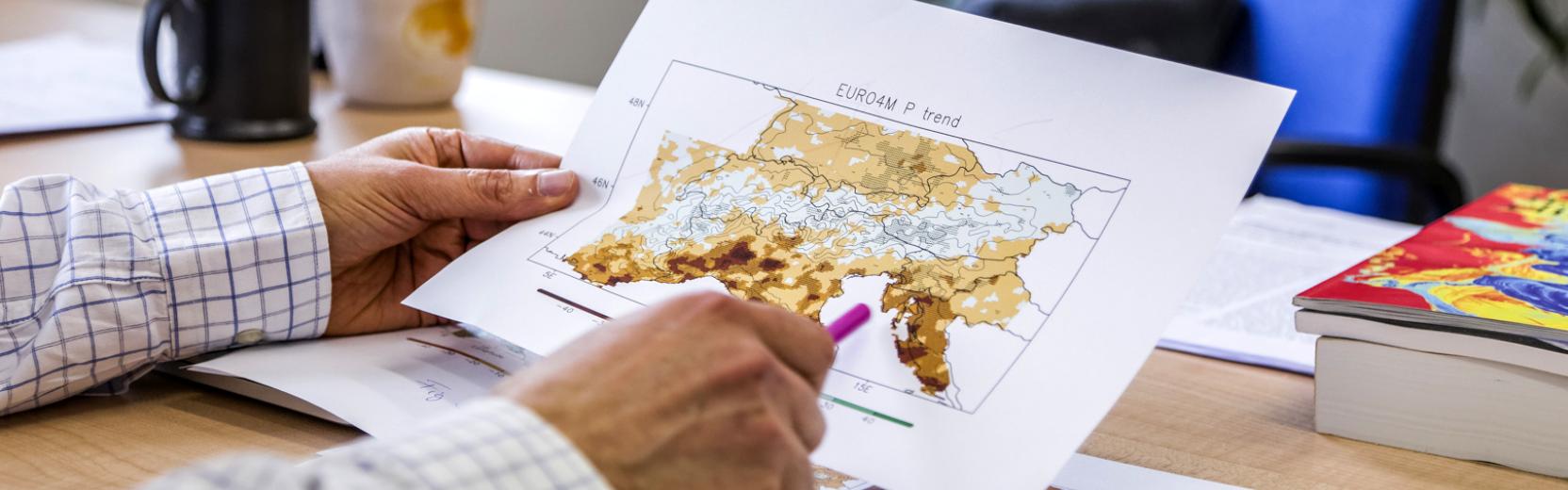

Secondly, one crucial step will be to revisit the way time measurements were carried out. The team used the global positioning system and precision caesium clocks to determine the time required by neutrinos to travel from the particle accelerator at CERN to the OPERA detector in Italy. "What I would like to know is how one can verify the synchronization of the clocks at CERN and at Gran Sasso Laboratory," says Smirnov.

Moreover, Smirnov points out, there are a number of theoretical aspects that raise red flags. For example, even if the neutrino velocity were faster than that of light, the difference to be expected would be much smaller than 60.7 nanoseconds.

Another point Smirnov draws attention to is that neutrinos cannot be considered in isolation, as they are, after all, elementary subatomic particles. "If indeed the neutrinos are travelling faster than light, we have to ask ourselves, why has associated effects of this superluminal velocity not been seen in other particles?"

And most importantly, the theory of relativity (wherein the velocity of light is considered to be the fastest) has worked extremely well in explaining many aspects of physics and given observable and verifiable results, says Smirnov. "If the results of OPERA are correct, we still need to consider why the theory of relativity has been able to answer the questions it has, and that too with experimental backing."

"The interpretation of OPERA results in terms of superluminal neutrinos may be proven wrong on further investigations, but these results have given physicists an impetus to work on newer areas," says Smirnov, adding, "In the course of the investigations, physicists may make other landmark discoveries and increase our understanding of different phenomena. That is what is important."