Haiti, ranked consistently as one of the world's poorest

countries, could hardly have been less prepared for the disaster

that struck there on 12 January 2010: a 7.0-magnitude earthquake

that claimed the lives of an estimated 316,000 people and left

nearly 1,000,000 homeless.

Now, two years after the devastating event, Haiti continues to

struggle back to a semblance of normalcy. In its capital,

Port-au-Prince, streets remain partially covered with rubble; many

residents still live in crude shanty towns just a stone's throw

away from the once-grand Presidential Palace, itself still in

ruins.

Indeed, the general condition of post-earthquake Haiti could be a

metaphor for the state of science in that country. With an eye to

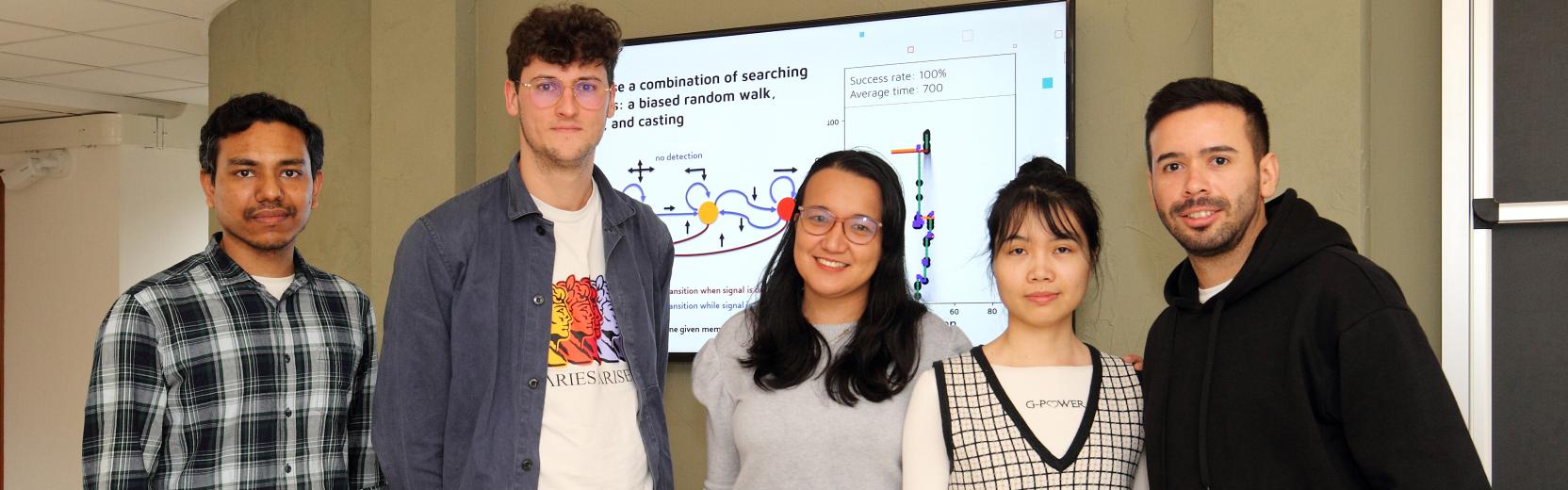

nurturing basic sciences in Haiti, ICTP recently held a school on

seismology from 15 to 28 January 2012. Organized by Karim Aoudia,

an earthquake expert in ICTP's Earth System Physics group, and with

the local help of the Faculte des Sciences of the Universite d'Etat

du Haiti (UEH) and the university's rector, Jean Vernet Henry, the

two-week school offered an intensive course on the full spectrum of

earthquake sciences, from physics to risk reduction.

Aoudia has run such workshops in other earthquake hot spots around

the world, including Africa and Central America. Typically such

courses would attract students and young scientists in fields

ranging from basic to applied sciences. But in Haiti, those

disciplines do not exist.

"The situation for science in Haiti is bad," said Aoudia, "there

is no money to support it, no local expertise, and few incentives

to keep professors in the country." What few professors they do

have will be retiring in the next few years, presenting an urgent

need to train their replacements.

Perhaps most surprisingly--for a country straddling the

intersection of the North American and Caribbean tectonic

plates--there are no seismologists in Haiti.

Aoudia hopes to change that, and the school is a small step in

Haiti's long road to recovery. "The long-term issue is to build

basic science capacity in the country," said Aoudia, noting that

currently there is no possibility to earn a science degree in

Haiti. Two years after the earthquake, efforts are still focussed

on rebuilding the infrastructure to support education. At UEH,

where the earthquake workshop was held, classes meet in hangar-type

structures open to the elements. There are no walls between

classrooms, and a bustling market in front of the campus adds to

the high-level of background noise competing for the students'

attention.

With the help of UEH staff, Aoudia was able to secure 20 computers

with a steady power supply. Participants, mostly from UEH's

engineering programme, learned the theory behind earthquakes and

how to read and analyse data sets on Haiti earthquakes that

occurred during the weeks of the workshop. They also gained

information on life-saving actions to take should an earthquake

strike; Aoudia said that the students were keen to spread this

knowledge. "They told me that one of the first things they will do

after the workshop is visit all of the schools in Port-au-Prince to

instruct young Haitians on what to do if there is an earthquake,"

he said.

In addition to sponsoring the Port-au-Prince workshop, ICTP has

donated 150 science books to UEH (they are starting a new library),

and is actively recruiting Haitian students for its Postgraduate

Diploma Programme.

But much more is needed if Haiti is to grow a science program that

could help alleviate its overwhelming poverty. Although the

2010 earthquake may have focussed the world's attention (and

much-needed funding) to the Caribbean island, momentum from that

wave of goodwill is slowing, according to Aoudia. "We need to

encourage more activity now before people forget about the problems

that still exist in Haiti," he said, adding, "Science can play an

important part in Haiti's long-term sustainable development."