Physics is a field divided into two branches: theory and experiment. ICTP's specialty is the mathematical-abstraction-filled world of theory, instead of the empirical-data-focused world of the experimentalist. But, while they have deeply different methods, the two branches complement each other -- it takes the work of the experimental physicist to determine whether imaginative theories reflect the truth.

ICTP condensed matter physics diploma student Amna Abdalla Mohammed is a problem solver who enjoys experiment more than theory. She prefers the collaborative process of sharing information and working in groups of people who have a broad variety of knowledge. Theorists need to focus on their imagination, said Mohammed, but with experiments you can get tangible results, sometimes even accidentally. "I like experiments because our life is a big experiment," she said.

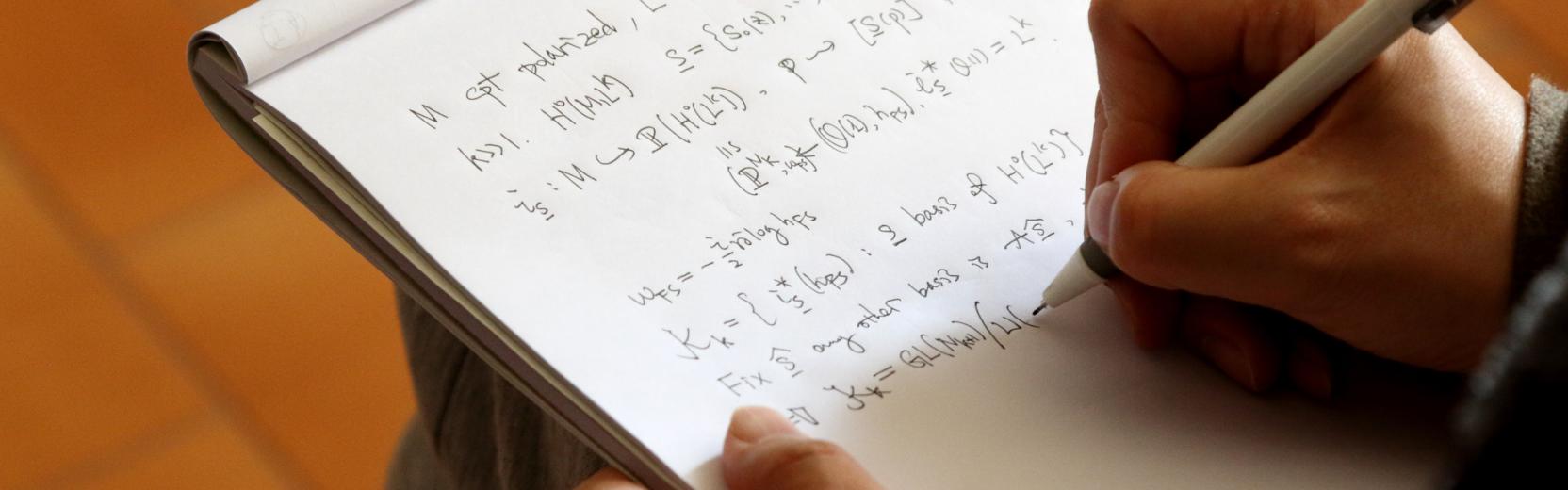

But in order to do experiments she needed a strong theoretical foundation. That is what Mohammed says she has gained from ICTP. Another benefit of ICTP is that professors and lecturers here explain the reasons and origins behind experimental results of physical theories.

In her home country Sudan, Mohammed studied general physics and worked as a teaching assistant and tutor. She was working on a master's degree in material sciences when ICTP accepted her into its postgraduate diploma programme, and she interrupted her studies to come here. She studied basic physics during her first year at the centre mainly to benefit from the higher caliber of education available, but also because of the challenges of breaking through the language barriers -- in Sudan she had done all her studies in her native language of Arabic. After completing her basic physics studies she was accepted into the condensed matter programme and will soon be finishing her studies.

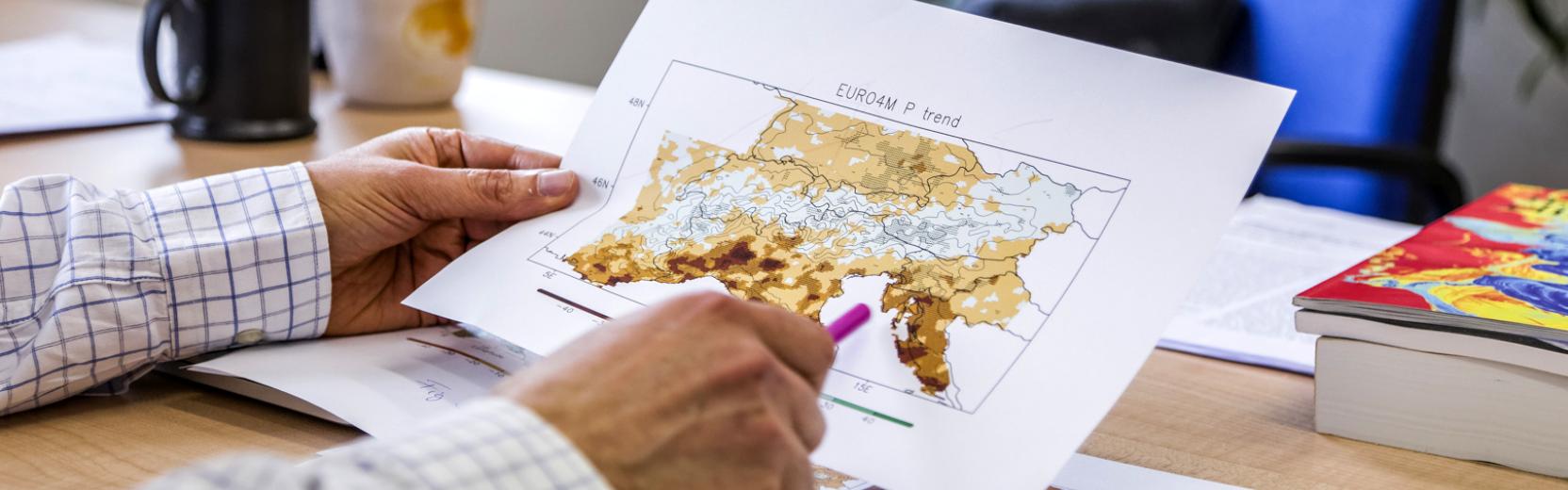

Mohammed wants a career in nanoscience, and is contributing to research at Synchrotron Trieste, a free-electron laser light laboratory. Her experiments have a biological aspect; she studies how DNA interacts with certain proteins. She uses a tool called atomic force microscopy to create images of DNA and protein molecules while genes replicate themselves.

A problem for Sudanese science is there simply isn't much money to support researchers. Mohammed said that Sudanese scientists are more likely to work for companies than in academia because professors need to work extra jobs to make ends meet. Regardless, she hopes that someday it will be feasible to be a scientist in Sudan so that she can return. "When I finish my Ph.D.," she said, "I want to go back to contribute my knowledge to my country."