Modern humans are the only species still alive that fall within

the genus Homo. Our relatives, such as Homo erectus and

Homo habilis, emerged, mated, migrated and died out all

within the last 2.4 million years, and we have little more than

excavation sites and fossilized remains to piece together what

happened.

One burning question is how diverse the Homo genus was.

Anthropologists estimate that at least ten other species once

existed, but their interpretations sometimes rest with a single

excavation site. Therefore, the uniqueness of each species remains

under debate;the Homo genus could be less, or more,

diverse. It all depends upon current species classification systems

and anthropologists' continuous hunt to improve them.

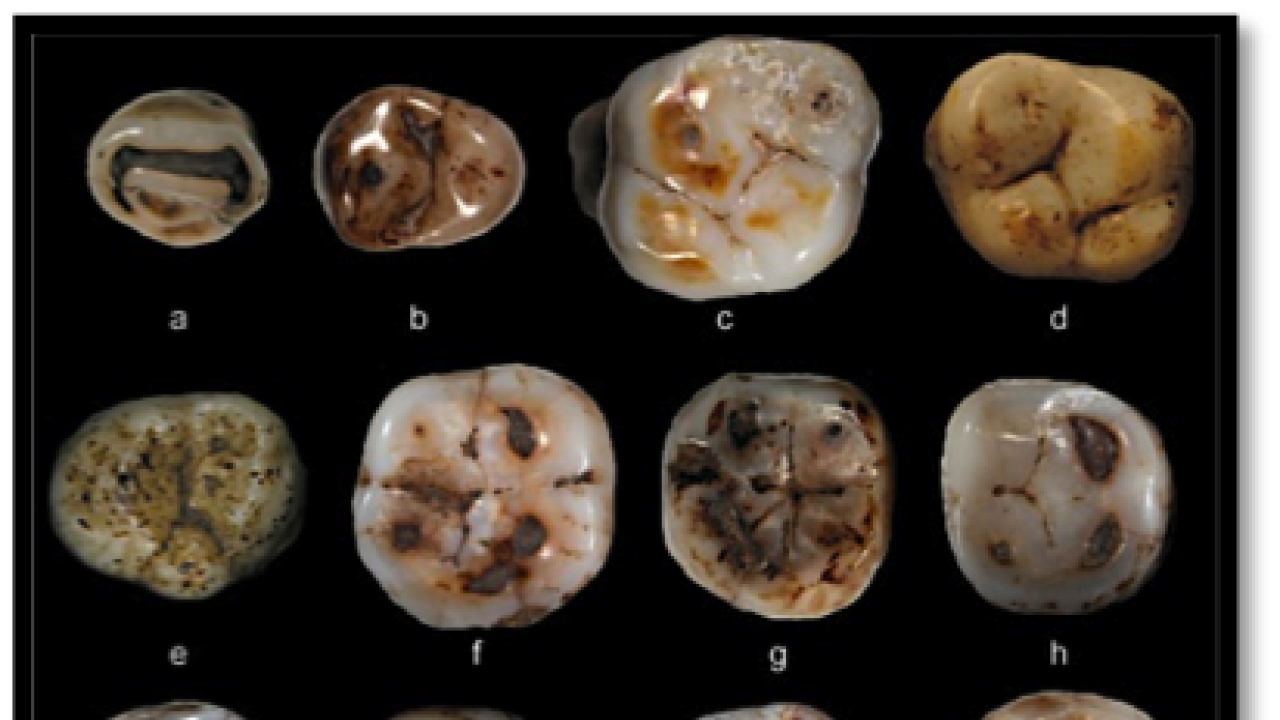

One such system, based on the size and shape of teeth, has been

the focus of Clément Zanolli's graduate thesis work at the National

Museum of Natural History of Paris, in France and now his

postdoctoral work at ICTP. The visible part of a tooth, called the

enamel, is what remains long after the roots, gums and surrounding

tissue decompose. Enamel can, therefore, fossilize for

archeologists to unearth millennia later.

"Teeth are very sensitive to genetic changes", Zanolli says. "This

means that each species has its own tooth morphology. However, it's

sometimes difficult to be sure and precise just by looking at the

enamel of a tooth because at times it is not well preserved."

Digging deeper for a solution, Zanolli and his academic advisors

in France applied a high-resolution CT (computed tomography)

scanner to a series of teeth from various species including

Neanderthals and Homo erectus. The CT scanner x-rays

the tooth, providing a complete 3-dimensional reconstruction of its

inner structure where the hard inner structure, called dentine, and

enamel meet.

"If you look at the dentine underneath the enamel cap, it's

preserved very well the characteristic grooves and indentations and

these reliefs are sharper than the enamel, allowing you to have

more precise elements to determine the species," Zanolli

says.

Zanolli's graduate thesis was the

first publication to include an analysis of the 3-D inner

structure of teeth from the species, Homo erectus. He

analyzed fifteen teeth, mostly permanent molars, uncovered in

Central Java, Indonesia. The size of the teeth varied greatly from

small, similar to modern humans, to large, similar to modern

orangutans.

At first, Zanolli was unsure which species to which the teeth

belonged, but the detailed 3D reconstruction gave him confidence as

to the samples' Homo erectus origins. The broad variation

in size, he argues, parallels some of the global climate changes

that affected Southeast Asia between 1.5 and 0.1 million years ago,

altering entire ecological systems including different

Homo species.

Zanolli discovered that some of the teeth were similar to

Homo erectus species found further north in Southeast Asia

and to some extent in Northeast Africa, suggesting that the species

migrated great distances and survived in different climates.

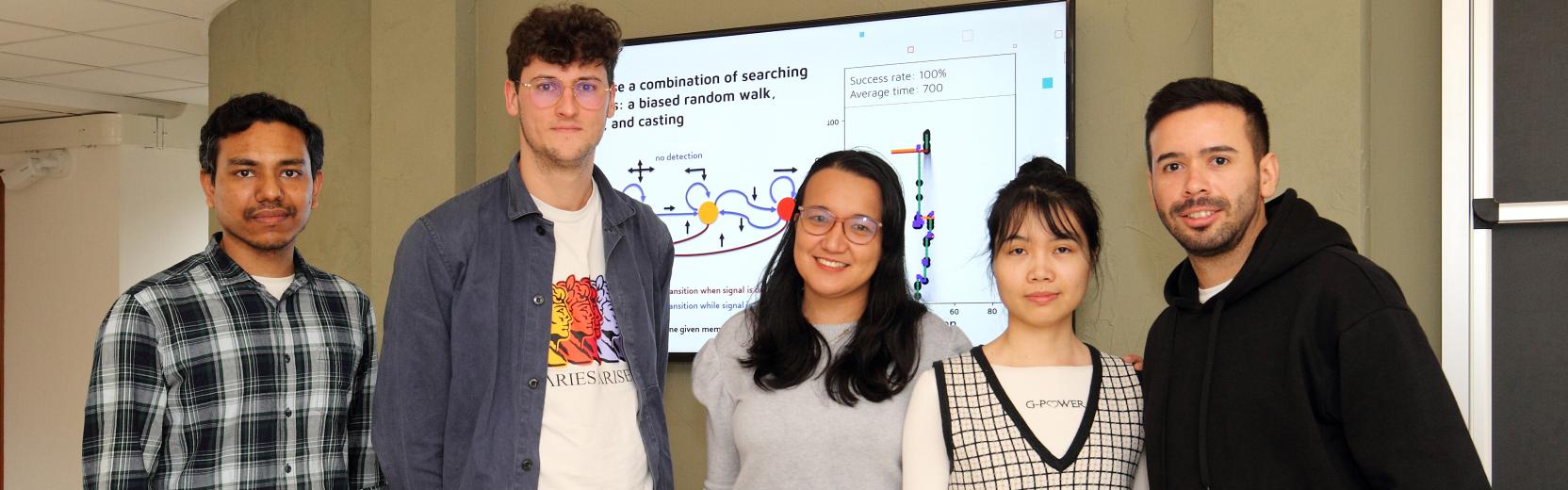

Zanolli continues to study the inner structure of different

Homo species at ICTP's Multidisciplinary Laboratory. Using

the Mlab's advanced X-ray microCT system, Zanolli is currently

reconstructing 3D images of fossilized teeth from Homo

erectus to Neanderthals and modern humans. Ultimately, he

hopes to construct a clear picture of the migratory patterns of the

various human species.

"There are a lot of ways to make a fossil, but it's a very rare

and arduous process," Zanolli says. "So fossils are like a treasure

that gives us just a little piece of the overall puzzle. I'm always

excited to work with new and different fossils."