With scientists for grandparents, a mathematician for a mother and a theoretical physicist for a father, it was no surprise when Nana Shatashvili and her brother became the third generation to uphold the family tradition and pursue a career in mathematical and physical sciences. But times were different growing up in the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic, part of the Soviet Union, and by the time Shatashvili was a working research scientist in the mid-1980s, Georgia was a country teetering on the brink of political turmoil.

"In a way, it was practically impossible for young researchers to travel and difficult to construct any collaborations with leading centers outside of the Soviet Union," Shatashvili recalls.

As a child, Shatashvili excelled in mathematics. Although she was one of the few females in her classes to do so, her gender did not affect the opportunities, stipends and scholarships she would later receive in her pursuit toward a career in physics research. In fact, the Communist system encouraged and upheld equal opportunities for women and men. As a result, Shatashvili and her female colleagues comprised about one third of the scientific staff in Tbilisi State University, where she worked as a junior and eventual senior research scientist throughout the 1980s and early 1990s.

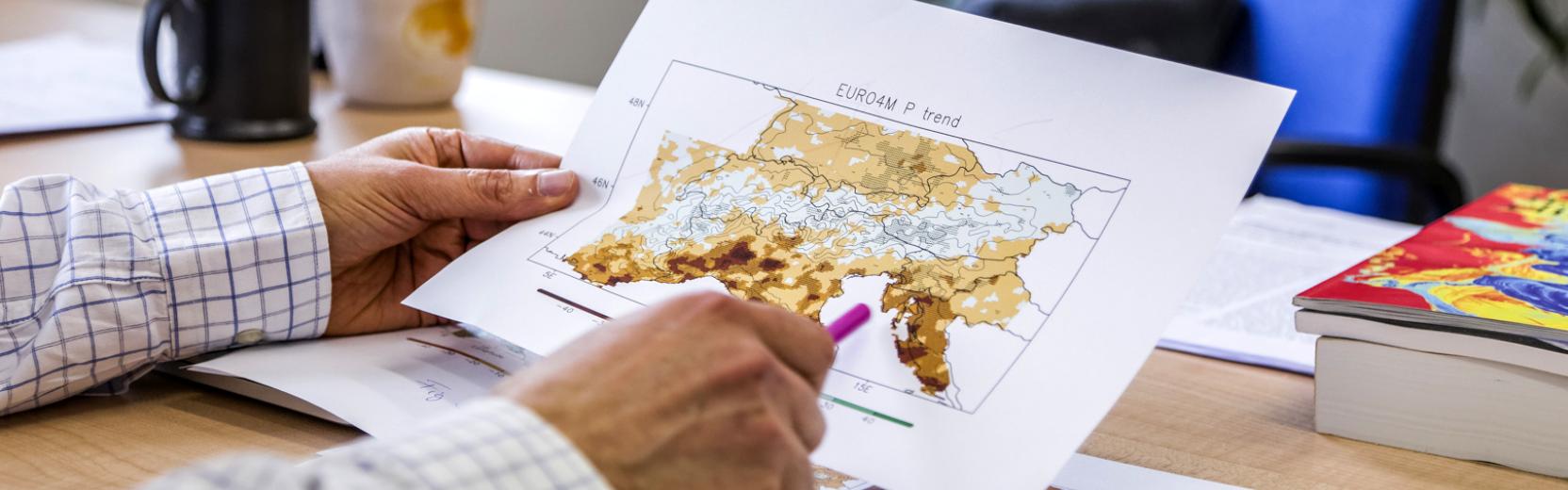

At that time, Shatashvili was a theoretical physicist researching hydrodynamic fluids. She knew her interests reached beyond theoretical modeling, but the inability to explore different topics with collaborators from various backgrounds and disciplines left her probing for which direction to take. When Georgia declared its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, the border regulations disappeared and doors of opportunity opened for scientists like Shatashvili. Four years later, she visited ICTP for the first time, where she developed an interest in solar plasma astrophysics, the topic she continues to study today.

"To be successful in science, it is important to have your own direction and be confident and independent," Shatashvili says. "I got the chance to start establishing external collaborations and the best way I did that was through working with the scientists at ICTP. They do very advanced science, which helped me gather new ideas and that was encouraging. ICTP helped me find my own direction."

Adorning the walls of her office at Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, where she is now an astrophysics professor, are posters from ICTP conferences she's attended over the last 15 years. She often refers to them when discussing her experiences at ICTP with students and colleagues. As important as finding her direction in research was at ICTP, she says, the centre did even more by boosting her self-confidence in her abilities as a scientist. And confidence is a trait that people will notice beyond gender.

"I have had little trouble in my career in terms of my gender. But, if I would have had problems as a woman, that was cancelled because I was confident in my abilities," she says. "When you get to a certain level in your field and are confident and independent with your research, no one questions if you're a woman."

The budget cuts and reforms that came about in 2005 due to political changes in Georgia, drastically reduced the number of positions available for research scientists and thus the number of men and women willing to pursue a career in scientific research. Today the numbers are improving, but Shatashvili sees more women studying math than physics at Tbilisi State University because of the teaching positions they can obtain immediately after completing school. The few women that do study physics, however, are as equally competent as the men and are given just as much opportunity, she says. In fact, one of her former female students, Mariami Rusishvili, is attending the ICTP Diploma Programme for the academic year 2013/14, which began this September.

"When scientists in society are not valued, then it is very difficult for anyone to study science," Shatashvili says. "But Georgia recognizes science and so it should not matter what gender you are or what background you have as long as you possess the underlying curiosity that is what drives scientific research."