The lecturers at last week's joint ICTP-IAEA Workshop (on Determination of Uncertainties of Measurements in Medical Radiation Dosimetry) are members of a peculiar club. Smiling in the workshop's group photo, they wear shirts that proclaim them as members of the "Association of Uncertain Scientists." However, they're certain about one thing: the importance of standardizing uncertainty measurements in medical radiation.

"It's important to homogenize the treatment of uncertainty worldwide," said lecturer Costas Hourdakis of the Greek Atomic Energy Agency. "There needs to be a common process, a common language for dealing with uncertainty."

Radiation is commonly used in modern medical practice around the world, both as a diagnostic tool and as part of therapy. Yet ignoring the uncertainty inherent in the dose can result in a patient getting too much or too little radiation and thus improper treatment.

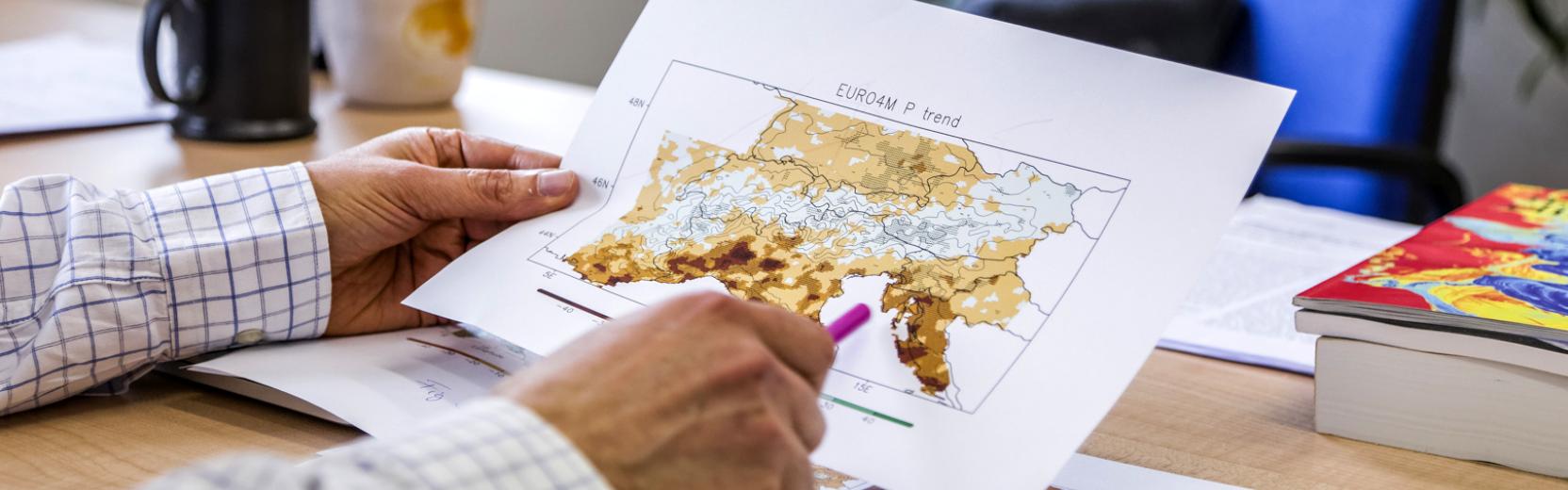

Uncertainty does not mean that physicists or physicians don't know or understand how to use radiation properly. Rather, because of the inherent nature of radiation and the instruments used to deliver it, there is always a chance that the dose will be slightly different from the one intended, and the size of that difference is the uncertainty of the dose. Sometimes the uncertainty in the dosage is less than 1%, but it can be as large as 25%, said Brian Zimmerman, a conference director and lecturer from the United States' National Institute of Standards and Technology.

"The final result is that it affects the patient," said Larry De Werd, one of the conference directors from the University of Wisconsin Madison. "The treatment outcome is one-to-one related" to the understanding of uncertainty, agreed lecturer Tony Aalbers of Delft University in the Netherlands.

Ahmed Meghzifene of the IAEA organized the conference so that practitioners around the world could "be aware of the concept of uncertainty." In the slides of his opening presentation for the workshop, he stressed that "a good measurement may be meaningless without knowing its uncertainty."

While the IAEA and ICTP have held workshops on medical radiation before, this is the first time a week-long workshop has focused exclusively on discussions of uncertainty in the dose measurements. Meghzifene chose to run the conference jointly with ICTP partly because of the number of academic visitors to the Centre. The idea for the workshop was to train people from around the world who can go back and teach concepts relating to uncertainty at their home universities.

The 49 conference participants came from a number of fields and 34 different countries. One-third of participants were medical physicists working in hospitals, one-third were students, and 20% were radiation physicists working in standards laboratories in their home countries. The remainder of the participants were ICTP affiliates, including current master's students in the new ICTP two-year master degree programme in medical physics, which began in February 2014 in cooperation with the University of Trieste. Applications for the second cycle of the programme are open until August 31.

The diversity of the participants' areas of expertise also created a rare opportunity for networking across fields. "It's extremely rare to have interactions between a standards lab and a hospital," Zimmerman said. Conference participant Maria Laura Haye from Argentina agreed. She works in medical physics, and found it was nice to share experiences with scientists in related fields.

Meghzifene hopes to run the workshop again in the future, encouraging even more practitioners from around the world to join the ranks of the "Association of Uncertain Scientists" and improve patient care through better scientific understanding of uncertainty.