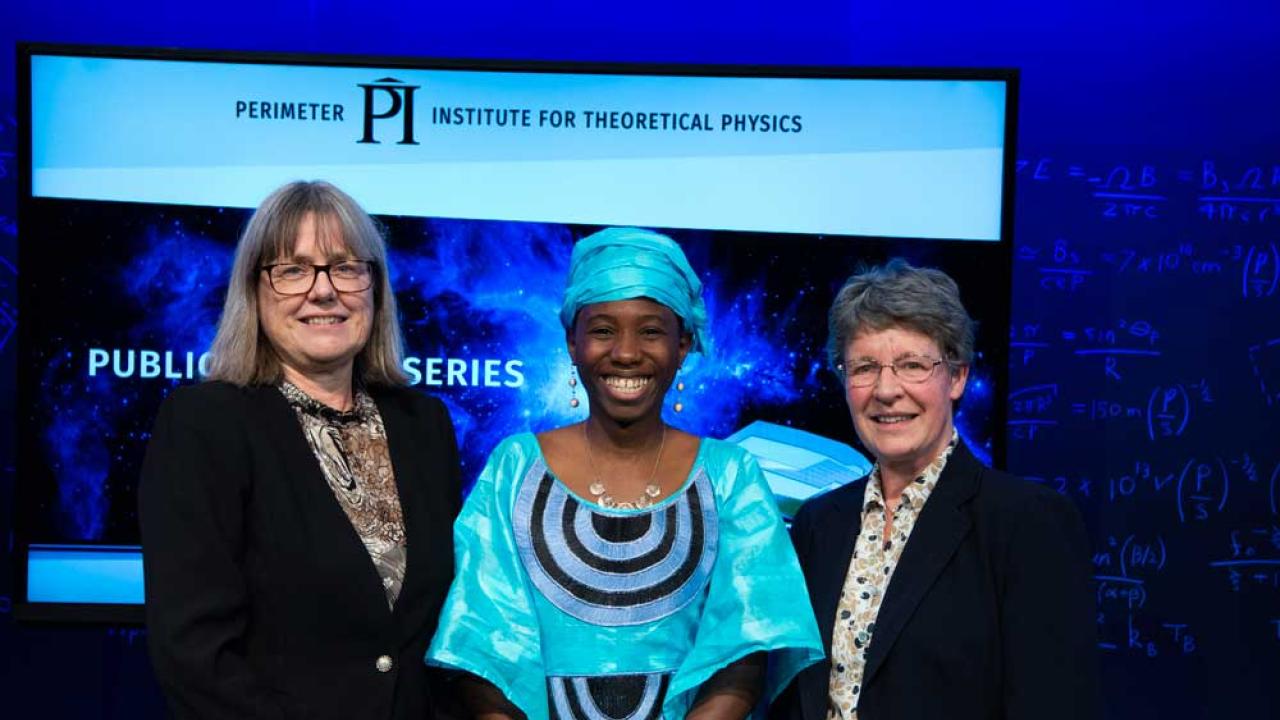

Estelle Inack is exuberant. An alumna of ICTP's Postgraduate Diploma Programme who recently completed her PhD through ICTP's joint doctoral programme with SISSA, Inack is poised to begin a postdoctoral position that will give her extensive freedom to investigate different aspects of the burgeoning field of quantum computing. As the first recipient of the Francis Allotey Fellowship, which honors the late distinguished Ghanaian mathematician, at the Perimeter Institute in Waterloo, Canada, Inack will have funding for four to five years. And there she already knows what some of her next steps will be.

“Part of my PhD was developing projective quantum Monte Carlo methods, effected using neural networks, and I want to find how to make that method really optimal,” Inack says, describing the project that led her to dive into machine learning. “The second thing is really applying machine learning to quantum many-body systems, which is what Roger Melko, who I will be working with at Perimeter, is really an expert on. And then many things related to machine learning. How can a quantum computer boost machine learning?”

These are hot topics, and not just theoretical, says Inack. A lot of companies are now building quantum computers, starting with small 16 qubit ones with plans for 72 and 128 qubit computers, constantly expanding the possibilities. “It’s really amazing what these companies are doing,” Inack says. “There is a whole building of everybody working on quantum computing, but from different fields. You have mathematicians, computer scientists, physicists, you have engineers, experimentalists, machine learning experts, all working together, all talking to each other, and everyone speaks your language.”

A lot of young scientists have to decide, at some point in their career, if they want to try to stay in academia or to find what type of industry position could work for them, something in the back of Inack’s mind. “In academia I have the freedom of exploring what I want to do, and collaborating with the people I want to collaborate with. But I would also very much love to have an experience in one of those big companies, to really see how they work practically, how they build a quantum computer.” Regardless of the academia versus industry choice, Inack is quite excited about the field. “I’m in a field that is at its beginning, and there are a lot of things to do, to try to understand, a lot of things to test.”

With a great career ahead of her, Inack did not initially want to be a scientist: instead, when she was young, she was hoping to go into naval architecture. “Then it turned out that I could not do naval architecture with a Bachelor’s in Physics, and I could not do a Master’s in Computer Science because my university didn’t yet offer one. So I did a Master’s in Physics.” Inack continued in physics by coming to ICTP’s Postgraduate Diploma Programme in 2013, focusing on condensed matter physics. From there, her ICTP advisor Sebastiano Pilati turned her attention towards quantum computing, and her Diploma thesis evolved into her PhD work at the ICTP-SISSA PhD programme.

“Can we, as we believe, solve problems with quantum computers that we cannot with traditional computers? I would also like to get into quantum algorithms, because at the end of the day if you have quantum computers you really need algorithms to run on them, quantum software. The potential ability to tackle real world problems with quantum computers, that’s really what drives me.”

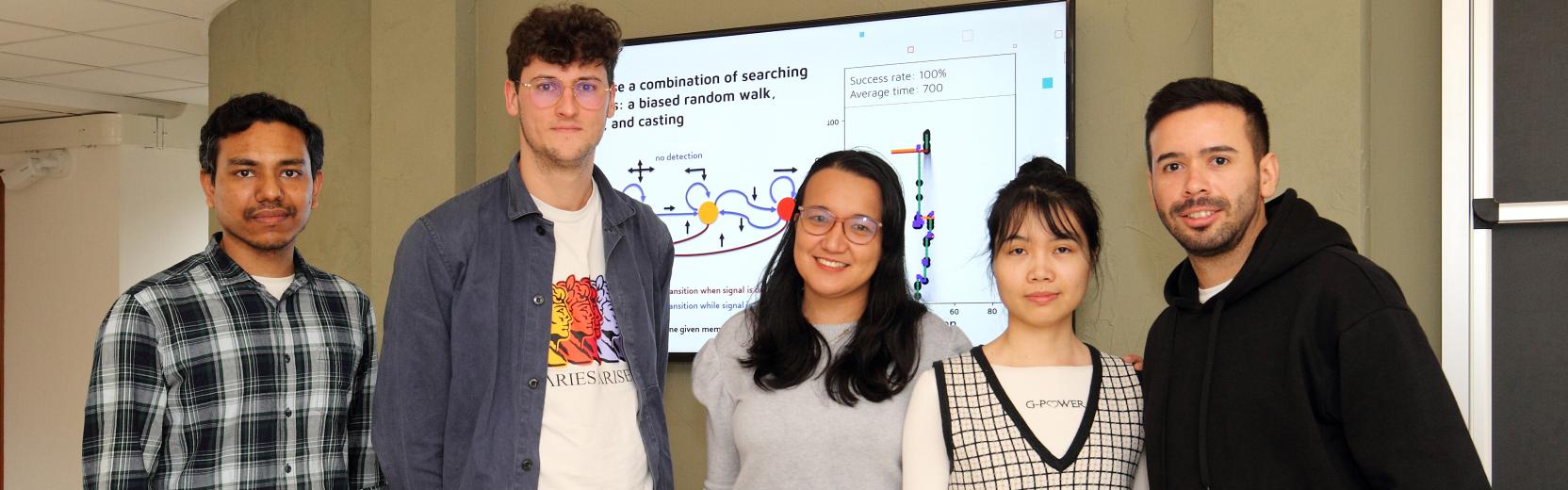

As Inack transitions from ICTP to the Perimeter Institute, she took time to attend the opening ceremony of the new ICTP partner institute, the East African Institute for Fundamental Research (ICTP-EAIFR). A native of Cameroon, Inack also attended two accompanying events, a Workshop for Women in Science and a meeting on Reviving the African Physical Society, which was also a tribute to Francis Allotey, for whom her Perimeter Fellowship is named. Both of the events involved dedicated and talented scientists discussing how to fuel and support the growth of science communities on the African continent, something that Inack thinks about often.

“My father was the one really pushing for me to do a PhD in physics,” says Inack, describing how her father wanted to do a PhD in physics, but went into engineering in order to not risk a scholarship. “Some other family members were more looking at the reality in Cameroon, where physicists are not well considered or respected in society, it’s more the engineers,” describes Inack. “So they were saying to go into engineering, something more practical that can also bring personal fulfillment.” But as her career developed, they started seeing that it was both a meaningful and successful career for her. “There has been a phase transition in what they think!” laughs Inack.

“People are not aware that being a scientist in Europe and the US is not the same thing as being a scientist at home, it’s a totally different thing,” Inack explains. “A scientist in Africa is somebody who teaches and maybe does research. And even then they have to struggle a lot to get funding, and the environment is not the best. Most of them stop doing research and start teaching at private schools, just to have something at the end of the month. So it’s not a profession that is respected.”

Often, the measure of success for an ICTP programme is how many scientists return to their home countries to develop science communities there. But there are other ways, sometimes more effective, to build scientific capacity. “I started thinking, is the best way for me to help my country being home physically?” says Inack. “And the answer is no, at least for the next five years.”

“There are a lot of things that maybe you could deal with when you return home to do science,” Inack says, “like a salary that is roughly 20 times less than a salary abroad. But the resources available— how do I run my simulations? Here I was running my simulations on computing facilities that apparently cost two million euros a month for electricity. Who’s going to pay for it? I would feel terribly bad asking the government to pay for it when there are people who do not have access to clean water or electricity.” Internet access is also an issue, with little funding for connectivity, as is access to scientific journals, which charge steeply for scientists to read what is going on in their field. Without funding for science, traveling to work with collaborators and going to conferences is also impossible. “That’s the reality, there are a lot of obstacles,” says Inack.

Inack hopes to be able to attract independent funding from outside sources in order to carry on her research when she returns home, and she hopes the postdoctoral position in Canada will get her closer to that goal. “But you can build bridges,” she says. “I believe there is a whole range of things we can do from outside Cameroon, like organizing conferences there, finding funding and bringing international people in.” Science communication to the public and young students is another way to build a strong future science community, Inack says, “to inspire the next generation. And you can go home to teach, to build collaborations locally, to invest back in Africa by applying for funding and collaborating with institutes and scientists there.” Inack is hopeful about the impact she can have as a rising star in quantum computing. “There are so many ways to be involved in developing science in Cameroon beyond physically being there.”

---- Kelsey Calhoun