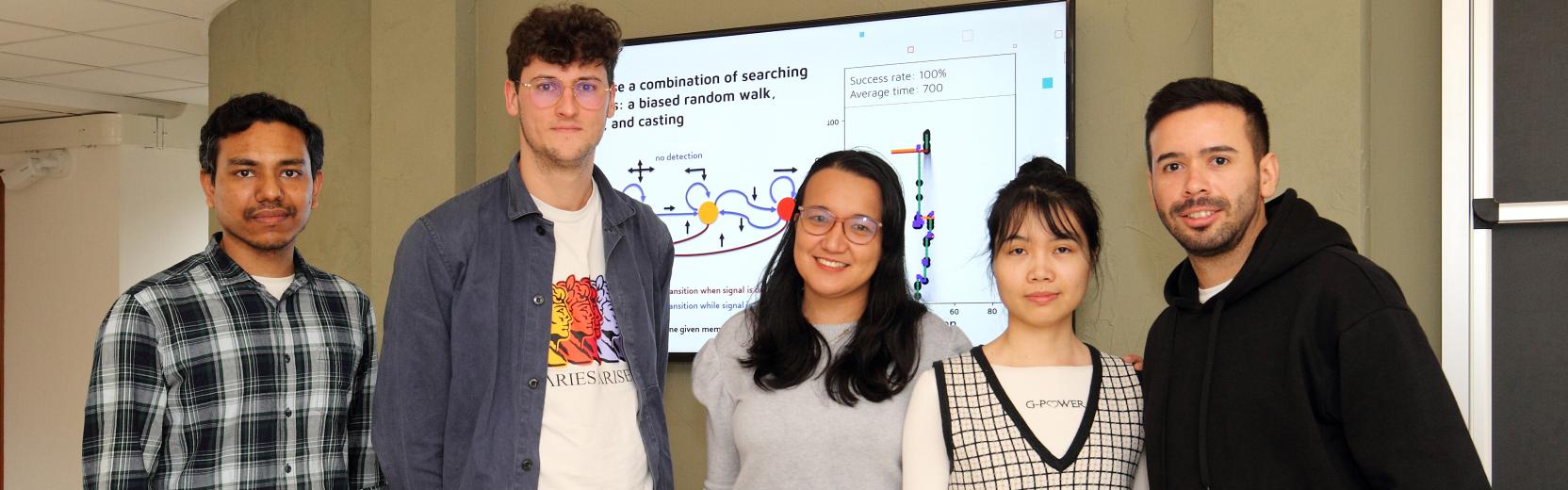

At a recent ceremony marking the graduation of ICTP Postgraduate Diploma students, a microcosm of ICTP was on display. The 43 graduates from 27 countries reflected the cultural diversity ICTP is known for; indeed, many of the scholars had donned clothing from their native countries. The diplomas they received acknowledged their achievements in mastering theses in ICTP's many research areas. With their newly gained knowledge, and a boost of confidence from having completed the Postgraduate Diploma Programme, the scholars are ready to begin the next stages of their science career journeys.

But before they scatter across the globe to begin masters or PhD degrees, ICTP met with several students to get their viewpoints on the Postgraduate Diploma Programme, the state of science in their home countries, and what their future plans are. Their stories follow.

Younes Benyahia, Algeria

Arpon Paul, Bangladesh

Rolando Ramirez Camasca, Peru

Amelia Sanchez Perez, Cuba

Kyrell Verano, Philippines

Younes Benyahia, Algeria (Diploma in Mathematics; admitted to ICTP/SISSA Joint PhD Programme)

I come from Algeria, and the science situation there is not very good, especially in mathematics. For starters, there's no special school for math, to do math you need to go to a regular university and usually not a good one, yet for other disciplines some of them have high schools. There's no special research institute. If you are doing science or math, you will mostly only have the chance to teach rather than research. As for the students, the brightest ones all opt for engineering or medicine, which is the case everywhere, I presume, but I think it's to a higher extent in my country.

I come from Algeria, and the science situation there is not very good, especially in mathematics. For starters, there's no special school for math, to do math you need to go to a regular university and usually not a good one, yet for other disciplines some of them have high schools. There's no special research institute. If you are doing science or math, you will mostly only have the chance to teach rather than research. As for the students, the brightest ones all opt for engineering or medicine, which is the case everywhere, I presume, but I think it's to a higher extent in my country.

I was into math since I was young; I was always fascinated with the deductionist method of math, rather than the scientific method of biology or physics. The point where I decided to do math was in high school, where I was selected for the international Olympiad, and that's what made me see math beyond the routine boredom of high school.

There's some societal pressure for not choosing [a field of study] more effective. My grades allowed me to choose anything, but I went for math. My parents were always supportive. Another challenge was to balance between following my academic grades and acquiring a good training on my own. For example, in high school I had to balance between my high school training and academic grades and my Olympiad training.

There's hope in my country that next year they will open a new school for mathematics, the first one. There are also a few non-governmental initiatives, one being the international Olympiad, and the other initiative is called Math Win, led by an Algerian professor working in France to provide more solid training for good university students, organizing math camps and reading groups and so on.

There is a very good environment here at ICTP for science. Everyone is discussing math and physics. The professors are so friendly, you can have coffee with them while you casually talk about math. It's surprisingly very diverse, a lot of fields of mathematics are covered here, even if there are just a few faculty members. Whatever you like, you can find it here.

While I am working on my PhD over the next four years I will also try to help with those non-governmental initiatives I talked about in my country; in the long term, I would like to get even more involved with them and continue to work toward an academic research career.

Arpon Paul, Bangladesh (Diploma in High Energy, Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics; admitted to PhD, University of Minnesota, USA)

Most of the students in Bangladesh who are very bright don't get the proper opportunities in the universities for research. For example, the professors in our universities must spend a lot of time teaching. In US universities there are teaching assistants, but in our universities there are no teaching assistants. So the professors don't have enough opportunity for research. Also you need a lot of PhD students and postdocs to have a strong research group, but in our university there are no postdocs in the physics department, and also no PhD students. The brilliant students tend to settle in the US or Europe where they can get these opportunities. There is not the environment in Bangladesh to allow them to use their full potential.

Most of the students in Bangladesh who are very bright don't get the proper opportunities in the universities for research. For example, the professors in our universities must spend a lot of time teaching. In US universities there are teaching assistants, but in our universities there are no teaching assistants. So the professors don't have enough opportunity for research. Also you need a lot of PhD students and postdocs to have a strong research group, but in our university there are no postdocs in the physics department, and also no PhD students. The brilliant students tend to settle in the US or Europe where they can get these opportunities. There is not the environment in Bangladesh to allow them to use their full potential.

I had been interested in physics from early on, from when I was a teenager, but it is difficult, because of the background of Bangladesh, to have a research career in physics. Mostly what happens is that the good students tend to study medicine or engineering, but I thought that, because I love this topic, I want to solve problems, I really love to learn about this stuff. When I was in high school I attended physics olympiads and there I met a lot of physics professors and students who were working in physics. There I got an idea of the path I could go to be a physicist. Later I did my undergraduate in physics, and, here I am!

A challenge I have faced was when I was applying to PhD programmes. At my university in Bangladesh we didn't have an undergraduate thesis, and this was a negative point for my profile. Also, there are not many students from Bangladesh who are in the top schools, like MIT or Princeton, so universities don't know much about my background and don't know how to measure my profile. In Minnesota, they have had PhD students from Bangladesh in the physics department and that's how they knew what Bangladeshi students are like.

The Diploma programme was good, but one thing I should mention is that this year was an exception because of the pandemic. For example, I attended the whole first term of the programme online from my country, I couldn’t arrive at ICTP because of travel restrictions. This was a problem because most of the stuff we learn happens outside of the classroom, through discussions with professors or your classmates, so this was a big challenge for me. I was able to arrive for the last six months of the programme, and then I was able to have discussions with the professors, PhD students, postdocs, my classmates--these are the kinds of things that really help. The thesis I did at ICTP, I talked to PhD students and learned a lot from them also. ICTP offers an environment that encourages students to learn more and think more.

I will be starting my PhD in a few weeks, and usually in the first semester students have courses in quantum mechanics 1 or classical mechanics 1, but I talked to the professors here and told them that I already have a Diploma in high energy physics. I showed them my ICTP transcript, and they allowed me to start with more advanced courses like quantum field theory 2, a course that students usually have in the second or third year of study.

I found a wonderful community at ICTP. The Diploma students stayed in the Adriatico Guesthouse, we used to play ping pong and have lunch and dinner together. It was great to have all those people around.

Rolando Ramirez Camasca, Peru (Diploma in Condensed Matter Physics; admitted to PhD, University of California San Diego, USA)

To study science in Peru is generally seen as a bad career choice, because of low employability and a lack of financial support from the state. I looked into the numbers, and the country only invests 0.12% of the GDP in science and technology, compared with 2.8% in the US (source: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-03844-2). There are also systemic issues like lack of government support, an outdated educational system. This has led to an exodus of researchers: Peru is exporting its scientists to the world. If one wants to pursue a career in academia, one needs to go to another developed country, for example to the US, or Europe, for research opportunities that you cannot get in Peru.

To study science in Peru is generally seen as a bad career choice, because of low employability and a lack of financial support from the state. I looked into the numbers, and the country only invests 0.12% of the GDP in science and technology, compared with 2.8% in the US (source: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-03844-2). There are also systemic issues like lack of government support, an outdated educational system. This has led to an exodus of researchers: Peru is exporting its scientists to the world. If one wants to pursue a career in academia, one needs to go to another developed country, for example to the US, or Europe, for research opportunities that you cannot get in Peru.

I've been very fortunate in pursuing science education. I've always been supported by my family, both economically and emotionally, and also I have had opportunities to go outside of my country to study physics. I spent two months in Canada, and then did a master's in Brazil, and now I am here at ICTP. But this is not common in Peru, I am an outlier in the physics community in Peru. I believe the main problem for physics undergrads there is the lack of research opportunities. There are few research groups in Peru. Because of a lack of financial support professors mainly put their time into teaching duties instead of research.

When I was in high school I really liked physics and math classes, but there is this common thought in Peru that if you are going to pursue physics or math you will end up being a high school teacher, that's all there is. When I applied to university to start my bachelor’s I was actually afraid of that and I pursued an engineering career. But during the first two years of university I realized that what I really liked was learning new math and new physics, and how this could be applied to the real world. That's when I changed from engineering to physics.

Ever since I changed from engineering to physics my dream job had always been to have a joint appointment between a university either in the US or Europe and a university in Peru. I think that way I will be able to connect those two communities and exchange knowledge but also give opportunities to Peruvian or Latin American students to get to know the research that is done outside the universities outside the country.

I'm very happy that I got accepted to the Diploma Programme and that I was able to learn from the coursework. It has been very intense but also very rewarding. I think that the coursework is comparable to top institutions in the world. Research-wise, professors here do a lot of cutting edge research at the boundaries of physics.

The main strength of Diploma Programme is that it gives students who haven't had the opportunity before to research and get exposed to different physics topics. Because this is a really diverse programme it has broadened my perspective about different cultures. I am happy that I managed to meet so many different people who are now really close to me that otherwise I wouldn't have been able to know. This sense of community within the students is important.

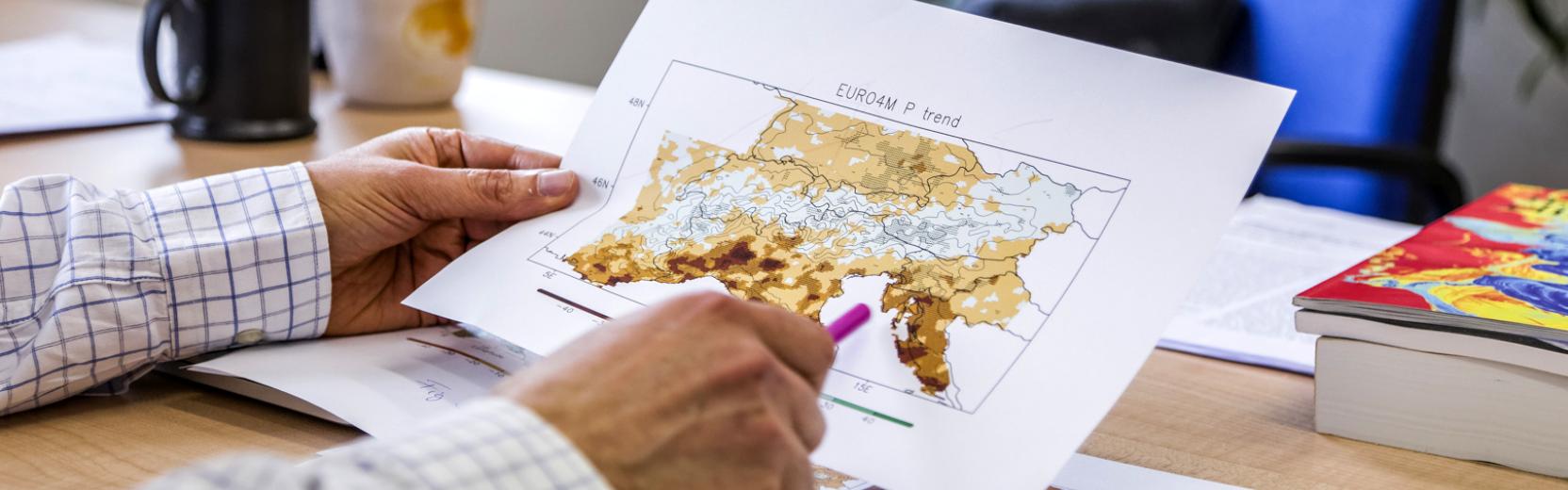

Amelia Sanchez Perez, Cuba (Diploma in Earth System Physics; admitted to MSc at National Polytechnic Institute, La Paz, Mexico)

Like many developing nations, Cuba has a lot of problems in science and research, for example trying to finance projects, or acquiring specialised scientific instruments. In Cuba, science research focusses on country priorities. That means that areas like medicine or biotechnology have much more development compared with other fields. For example, I am interested in oceanography, but in Cuba we do not have a university degree or a master's or PhD programme in oceanography. Scientists who do have training in oceanography have studied abroad. So it's really hard for young scientists like me to pursue lines of research different from the interests of the government.

Like many developing nations, Cuba has a lot of problems in science and research, for example trying to finance projects, or acquiring specialised scientific instruments. In Cuba, science research focusses on country priorities. That means that areas like medicine or biotechnology have much more development compared with other fields. For example, I am interested in oceanography, but in Cuba we do not have a university degree or a master's or PhD programme in oceanography. Scientists who do have training in oceanography have studied abroad. So it's really hard for young scientists like me to pursue lines of research different from the interests of the government.

I was interested in physics in high school, but I was more interested in General Relativity and Wormholes and all those cool things. Then when I got to university I discovered other parts of physics, for example climate physics, that I found really interesting, so I went deeper into the subject and did a thesis on the oceans.

The most difficult challenge I have faced was when I arrived here at ICTP, the language barrier. For me it was really hard, I had to speak in English every day and take classes and exams in English, I never took an English course, only basic lessons in school. It forced me to work hard to reach a level that allows me to have a good performance in the Diploma, and my friends were also supporting and helping me a lot with that.

The Diploma Programme exceeded my expectations. Here I learned a lot. I had excellent professors. And something important for me, in my field, is that I learned two programming languages, Fortran and Python. I think this knowledge will translate into a bright perspective for my future career.

I will stay on at ICTP to keep working on my investigation that I did for my Diploma thesis with my supervisor Riccardo Farneti. We want to write a paper. After that I will go to Mexico for a master in marine sciences, and eventually a PhD. I would like to return to Cuba to develop oceanography in my country.

The Postgraduate Diploma Programme is a programme of excellence, of course, but for me the most important is that the programme is also a multicultural space. Here I met wonderful people from other countries, people so different from me, and that was a great experience. I think the Diploma not only prepares you to be a good scientists but also prepares you for life in general.

Kyrell Verano, Philippines (Diploma in Quantitative Life Sciences; admitted to PhD, University of Trieste)

From my experience working as an instructor at a university, in our country there is a lack of support for science in such a way that the facilities are not sufficient, and it stifles research productivity. There is a lack of funding, and also a complicated process for procurement of equipment/materials. Actually, the national budget only gives about 0.15% GDP towards research and development. This is sad, because we need to improve our policies and innovations in such a way that it should be research-based.

From my experience working as an instructor at a university, in our country there is a lack of support for science in such a way that the facilities are not sufficient, and it stifles research productivity. There is a lack of funding, and also a complicated process for procurement of equipment/materials. Actually, the national budget only gives about 0.15% GDP towards research and development. This is sad, because we need to improve our policies and innovations in such a way that it should be research-based.

Some of our scientists prefer to work in other countries because they can have better salaries and more productive working conditions. However, it is good to know that there is a program in the Philippines that is bringing back the scientists (they offer more suitable environment and financial support) to share their expertise. Despite the insufficiencies or lack of funding from the government, the Philippines was still able to have brilliant scientists that are thriving to help and serve the country, some expanding their collaborations abroad to secure research funds. They strive to push research productivity and propose innovation-driven developments to our policy makers. They inspire me so much.

The science education also needs to be improved. From what I observed, you have to go to a science school or a good private school to be able to fully experience doing scientific experiments. There are schools in the Philippines where students never had experience to use a microscope, for example. In far-flung areas you had to rely on pictures.

I grew up in a village in the northern part of the Philippines. I dreamt to become a medical doctor, but to study medicine in the Philippines is very expensive, and we couldn't afford it. So I studied math. My bachelor's degree was in applied math, and my master's is pure math, but I really wanted to do applied research. I was introduced to biomathematics, a field in math where you apply mathematics to life sciences. I saw an opportunity where maybe if I cannot become a doctor I can contribute to research in life sciences. That's how I started to redefine my goals.

I wanted to apply to a PhD last year, but I didn't have the confidence to apply to a life sciences degrees because I didn't have any substantial biology or life sciences courses. So when I saw the call for the QLS Diploma Program I thought it was a perfect opportunity to prepare me.

The Postgraduate Diploma Programme has met my expectations; it is a very good preparation for a PhD. The QLS courses cover a lot, from ecology to biophysics to neuroscience to machine learning. It has opened a lot of learning opportunities, opening my eyes to different things so I can choose better what I would like to do. The professors are very helpful in every way – facilitating our learning and especially, patient to answer our questions. This learning experience made me more confident to be in science.

My long-term plan is to do work in academe near my home town in the Philippines. There is a growing research community there doing really interesting, impactful work. Joining this community, I wish to build a research team, hopefully to do significant research that can help the community, provide jobs for young scientists, and introduce them to a lot of learning opportunities in the world.

--Mary Ann Williams