The ICO/ICTP Gallieno Denardo Award annually honours young researchers in optics and photonics from developing countries who have made significant contributions to their field and promoted science and research through their mentoring or outreach activities.

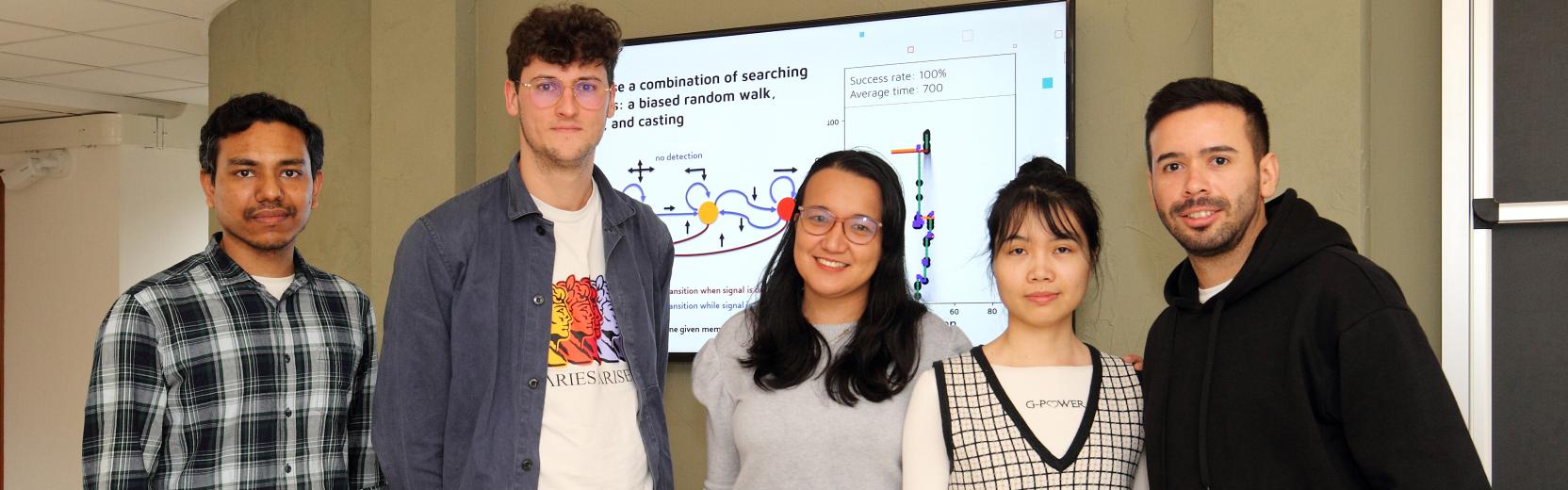

The winners of the 2025 ICO/ICTP Gallieno Denardo Award are Omnia Hamdy Abdelrahman Nematallah, from the National Institute of Laser Enhanced Sciences at Cairo University, Egypt, and Gustavo Grinblat, from the Faculty of Exact and Natural Sciences, University of Buenos Aires, Argentina, and the Argentine Research Council – CONICET. They were presented with the prize at a ceremony held on 4 March at ICTP as part of this year’s Winter College on Optics, organised by ICTP’s Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) Unit. Photos of the ceremony can be found on the ICTP Flickr page.

In this interview, the winners tell us more about the research that earned them the prize.

Interview with Omnia Hamdy

You received the ICO/ICTP Gallieno Denardo prize for your work in biophotonics and the development of innovative optical technologies for biomedical applications. Could you tell us, in just a few sentences, what biophotonics is?

Biophotonics explores how light interacts with biological systems, while photonics broadly investigates light’s interaction with any material. As a research area, biophotonics has developed at the interface between three different disciplines: science—including physics, biology and chemistry—medicine, particularly dermatology and ophthalmology—as well as engineering, particularly optical and biomedical engineering.

What are the most important innovative technologies you developed and what are their applications for public health?

My research primarily examines the optical properties of biological tissues, particularly their absorption and scattering coefficients. These two parameters are very important indicators of tissue health and can inform both the diagnosis and the treatment of many health conditions.

I also work on virus detection using laser transmission, a research line that I started during the Covid-19 pandemic. We study the optical properties of the viruses in solution and can tell if there is a virus and, if so, what type it is.

Another aspect of your work mentioned in the award citation is your strong mentorship of young scientists. Can you tell us more about the mentoring you do?

Helping students is my passion. What inspires and motivates me in doing this is the very positive experience I had with my PhD supervisor. She launched the biophotonics lab at my university and is now in Saudi Arabia, but we continue to collaborate. I would like more students to have a similarly positive experience, which is why I volunteer in many mentoring programmes in Egypt. One of them is STEM-Her Up, which helps female high school students who want to continue their studies in STEM. We help them develop their knowledge and soft skills. Another programme I volunteer for is Egypt Scholar, which is aimed at undergraduate students and provides them with advice on how to continue their studies. As a university professor, I also supervise several master’s and PhD students at Cairo University. I also advise students in other Arab countries, such as Iraq, who contact me because they are interested in my research.

What does this prize mean to you?

I attended the ICTP/ICO Gallieno Denardo award ceremony two years ago and, while I dreamt of being the winner, as I listened to his award lecture, I would have never imagined that this could happen. Winning the prize showed me that my hard work and my passion for helping others matter and get noticed. I tend to think that what I do is not important and that no one will see it. Receiving this recognition made me realise that people do care about what I do. It is a great motivation to keep going and it made me feel supported by the scientific community.

The prize is also a recognition of my role as a woman in science. During this Winter College I interacted with many young women from Africa who are passionate about science. They approached me to tell me that this prize has given them hope. I was very touched by their words and I hope that having a role model will motivate them to continue their journey in science.

I am also very grateful to ICTP. This is my second time at the Winter College and every time I come here I get important ideas that I can then develop in my research. This is the power of ICTP. I love coming here.

Interview with Gustavo Grinblat

You received the ICO/ICTP Gallieno Denardo prize for your important contributions to nonlinear and ultrafast optics. Could you tell us in just a few sentences what nonlinear optics is?

Nonlinear optics studies how intense light interacts with matter, resulting in a range of phenomena and processes. The most common ones affect the colour of light, or in more technical terms, its wavelength. It is called nonlinear because the efficiency of the process does not scale linearly with the intensity of the incoming light, but rather follows a power law. For example, in what is called second harmonic generation, the intensity of the output is proportional to the square of the intensity of the incoming signal.

And what is ultrafast optics?

The word ‘ultrafast’ means that something happens very quickly, but does not clarify what we mean by ‘fast’ in this context. In ultrafast optics we want to control a material’s optical properties at a timescale of the order of a femtosecond, that is 10^-15 seconds.

One of the main aims is to build ultrafast optical switches—devices that tell the signal when it can pass and when to stop. They are the most important components in a circuit. In commercial electronic circuitry, this role is played by transistors, which cannot go faster than a few GHz, due to the time it takes for the electrons to respond to the switch. When dealing with photons, switches can be much faster, reaching a frequency of a few THz or more. My collaborators and I have built prototypes that reach the order of 10THz. The problem with those is that they use a lot of power and are therefore not efficient enough.

What are the applications in telecommunications and information processing that you are most looking forward to?

All of my work is oriented towards building components for photonic circuitry. At the moment, we transfer and process information through electronic circuits, which are at the heart of all our phones and computers. They rely on the passage of an electric current—therefore electrons—through very tiny wires. We now want to control light—photons—with such high precision that we can use it to transfer and process information instead of relying on electronic circuitry. We expect several advantages from this, because light propagates much faster than electrons and the signal loss is smaller.

Currently, we are capable of using light to transport information only in open space or in optical fibres, which are big and take up a large space. In optical circuitry, we want to confine light to a very small scale—the nanometre scale, ideally, inside devices the size of a microchip. What makes this very difficult, is that light has got an intrinsic wavelength of about 500 nm on average, which does not allow us to confine it into smaller spaces. Most of my efforts are dedicated to squeezing light into very small spaces and to developing techniques that help us manipulate it at the nanoscale. For example, in addition to nonlinear and ultrafast optics, during the past five years I have also been working on ultrasound waves, which will help us convert optical signals into mechanical ones, something that we will need if we want to replace electronic circuits with photonic ones in our current technology. The real bottleneck remains that of confining light within extremely small spaces.

The prize also recognises your role within the Argentine optics and physics communities, and outreach activities aimed at high school students. Can you tell us more about it?

I represent Buenos Aires in the Argentine Physical Association, which promotes physics research and education in the country through various activities.

I am also part of the Argentine Optics Territorial Committee (ICO member), which focuses on optics research. When I first joined these associations I found it very difficult to contribute while pursuing my research and trying to find some work-life balance. Right now I am at a point in my life where I finally feel that I can and that I want to be more involved. I think that outreach is important for many reasons, including helping the public understand how science works and its impact on the real world. It is also important that, as scientists, we make an effort to convey what we do in ways that can be understood by non-specialists.

What does this prize mean to you?

This prize has certainly given more visibility to my work, but most importantly, it has given more visibility to the Argentine scientific community. Our country is going through a severe economic crisis, and this prize shows that we can still contribute to science at an international level. I hope it will inspire younger people and show them that they too can do great research in Argentina.

Another very rewarding aspect of winning the ICO/ICTP Gallieno Denardo Award has also been the opportunity to visit ICTP, where I had never been before. During the few days that I have spent here, I have realised what an amazing place it is.